Ebook Free We Have Been Believers

By reading this book We Have Been Believers, you will get the very best point to get. The brand-new point that you do not have to invest over cash to reach is by doing it on your own. So, exactly what should you do now? See the link page as well as download the e-book We Have Been Believers You could get this We Have Been Believers by online. It's so easy, right? Nowadays, modern technology actually assists you tasks, this on-line book We Have Been Believers, is also.

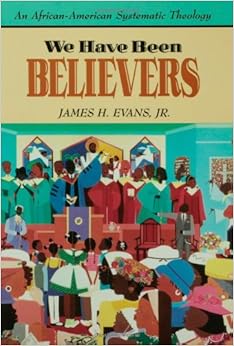

We Have Been Believers

Ebook Free We Have Been Believers

Don't you believe that reading books will offer you more benefits? For all sessions and types of publications, this is considered as one manner in which will certainly lead you to get finest. Each publication will certainly have different declaration and different diction. Is that so? Exactly what regarding the book qualified We Have Been Believers Have you found out about this book? Come on; do not be so lazy to recognize even more concerning a publication.

Well, what regarding you who never ever read this kind of publication? This is your time to begin understanding and reading this sort of publication style. Never uncertainty of the We Have Been Believers that we offer. It will bring you to the actually brand-new life. Even it doesn't mean to the genuine brand-new life, we're sure that your life will be much better. You will likewise discover the brand-new things that you never ever obtain from the other resources.

When beginning to review the We Have Been Believers remains in the proper time, it will permit you to reduce pass the analysis actions. It will certainly remain in undertaking the specific analysis style. However lots of people could be confused and also careless of it. Even the book will reveal you the reality of life; it does not imply that you could truly pass the procedure as clear. It is to really supply the here and now publication that can be one of referred publications to read. So, having the link of the book to go to for you is very cheerful.

Due to this publication We Have Been Believers is sold by on the internet, it will alleviate you not to print it. you could get the soft documents of this We Have Been Believers to save in your computer system, gizmo, as well as a lot more gadgets. It relies on your desire where and also where you will check out We Have Been Believers One that you need to consistently remember is that reviewing book We Have Been Believers will endless. You will have prepared to check out various other publication after completing a publication, and also it's continuously.

Product details

Paperback: 192 pages

Publisher: Augsburg Fortress Publishers (March 1, 1993)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0800626729

ISBN-13: 978-0800626723

Product Dimensions:

6 x 0.4 x 9 inches

Shipping Weight: 8.8 ounces

Average Customer Review:

4.7 out of 5 stars

5 customer reviews

Amazon Best Sellers Rank:

#797,807 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

What others need to know about us!

I appreciate the speed, quality, and price of this entire transaction. I would do this again if the opportunity presented itself.Thanks

Thanks for the prompt service. Book in excellent condition and received ahead of time.

A quick perusal of any major American conservative evangelical seminary curriculum will yield the familiar names of many systematic theologians: Wayne Grudem, Millard Erickson, Karl Barth and far many more. The commonality of these writings is that they are white men, sadly illustrating an unwritten standard in the evangelical world. In other words, what one doesn’t tend to find are voices of women and especially people of color. James H. Evan’s We Have Been Believers: An African-American Systematic Theology is a noble and worthwhile introductory treatment that is more than capable of filling the void. Evans writes on multiple issues including theodicy, the doctrine of God, ecclesiology, Christology and eschatology: all from an African-American perspective, and each topic yields surprising—and sometimes curious—results. His arguments are primarily influenced by the enactments of history, human experience and biblical interpretation. He commences this effort by beginning with multiple theological and ethical issues: African-American religion, narrative and slavery (24-31). If one has read through Christian Smith’s penetrating Divided by Faith it will come as no small surprise to read Evan’s contention that Holy Scripture has not only been hijacked to highlight the darkest segments of the human heart, but that this hijacking was seen as ‘normal.’ In light of this, he labels African-American experiences (oppression, violence, rebellions, etc.) as “paradigmatic†(6) of their story, which in turn yields the necessity of reading Scripture in a liberative fashion. The reality of evil plays a larger part in black theology—perhaps one of the highest roles imaginable: the reasons given are summed up in a subsection about Christianity and slavery (35-40) and the distinction of what Scripture ‘means’ and what it ‘meant’ (51). Scripture is given much breathing room, and human experience is manifested in Evan’s offering. He contends that no one comes to the text without experience; so to mute one’s narrative would be a disservice to the person. Instead, the necessity of story is that while it may have a specific and singular meaning, it can also be fleshed out and illuminated as we bring ourselves to this singular story. Evans notes, “No theology is “acultural†or value-free†(28). Because of this, the narrative of the person and Holy Scripture are meant to dance rather than sit on opposite ends of the room. It is not secret that for many, Holy Scripture is confused with one’s interpretation, born out of his or her own experience, and produced as the inerrant word of God. A private interpretation can become a substitute for the very Word of God. This should give any Christian great pause when interpreting a sacred text. Evans gives a sobering reminder of the personal trajectories of all readers of Scripture and what must be done in order to safeguard against imperialist understandings since “the Bible is a source of knowledge and inspiration†(27) the reader can struggle (through personal and structural oppression) towards liberation, towards a “redemptive narrative†(26). However, I do wonder if evangelicals can accept his method of interpretation, as for many conservative evangelicals, Biblicism is simply a wrought iron position, not to messed with or nuanced. The heavy Barthian language (27) is most likely not going to aide the more conservative student and the strong emphasis on human experience and history may strongly chafe against more sensitive American evangelical sensibilities. Perhaps this is a good and necessary thing.Evans moves onto the doctrine of God and Christology, powerfully illustrating the narrative of Jesus: born not in a castle, living a life of meagerness, living off the aide of his female patrons (Luke 8:1-3) are some penultimate examples that Evans draws upon in calling Jesus’ experience “symbolic of his existential condition…He is black because he was a Jew†(89). Jewish ethnicity plays a grand role in Evan’s Christology, as Israel was a slave beneath the shadow of empire, from Egypt to Syria to Rome; this brutalized Christ becomes a prototype (exemplar) that African-American theology has much to speak about, and even identify with. One wonders what Evans would do with the six-course feast of modern empire studies exemplified in the New Testament seen in the recent work by McKnight and Modica, Jesus is Lord, Caesar is Not. Moving onto anthropology, ecclesiology and eschatology, Evans is keen to speak on his own terms, leaving those of us who have little exposure to black theology (until now) struggling to keep up. Yet, anthropology and ecclesiology are linked, and Evans is determined to repeat that black theology is holistic in its outlook. Body and spirit aren’t divested of each other, but find themselves within each other. Evans sees doctrine not as separate entities, but as relational and connected. Orthodoxy, without orthopraxy, is dead. Then, as any good systematic textbook should, Evans ends his short treatise on eschatology. While most evangelical Protestants (such as myself) would expect a dogmatic rehearsal of the many multi-faceted phrases and images utilized by New Testament authors (fire, eternal punishment, heaven), Evans goes a different route. Theodicy and eschatology are closing linked, showcasing that the final defeat of evil must be front and center, as promised by a loving God who gives us hope (147). The nature of heaven and hell (or even the millennium) isn’t discussed, with Scripture taking a back seat to the discussion in favor of a summation of previous themes: the multidimensionality of hope and the nature of resurrection: the reanimation of flesh and spirit, and to constitute “one’s continuing existence in the presence of God and the company of saints†(153). The oppressed are vindicated, and persevere in spite of their troubles and turmoil’s, living out one of St. Paul’s final recollections in 2 Tim. 4:7: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race.â€There is much to commend about this little book. First and foremost, it is passionate and doesn’t pretend to be impartial to a specific point of view. Evans writes broadly and constructively, desiring to place the reader in the shoes of an African-American living in the United States, struggling to keep afloat and he succeeds admirably. One can feel the ripples of a life of immense reflection simmer throughout the pages. A second strength is his continual effort to marry an interpretation of Scripture with the human experience. In doing so, Evans will likely touch a nerve and deservedly so. Too often, experience is denigrated in evangelical circles, but in a post-Holocaust world we need to be reminded of Scripture’s power of influence, both for salvation and oppression. Thirdly, Evan’s inclusion and knowledge of the story of women in history is relevant for the evangelical debate on the equality of women. He hints upon some powerful points involving gender and creation such as God birthing the cosmos, but sadly doesn’t develop the point further. However, he does involve prominent women voices (47-48, 94) and it is evident Evans would fit securely within a feminist reading of Scripture and stalwartly supports the ordination of women (139). What makes this conviction especially important to systematic theology is that once one realizes that women share in the image of God (Gen. 1:26-27), where do they fit into the narrative of history and Holy Scripture? Evans doesn’t explicate, but the inclusion of the fairer sex is itself a step in the right direction.I had several questions and critiques but most of them quickly faded upon an additional reading, but allow me to present the three that have most stuck with me. First and most importantly, there is little in the way of Trinitarian thought in Evan’s work. The Holy Spirit is briefly mentioned (127-28), though the doctrine of pneumatology isn’t developed to any real extent, unlike Evan’s chapter on Christology. This is troubling, especially in light of much of Evan’s comments regarding Christology, where Chalcedon and Nicaea don’t factor into his thinking and their relevance seen as more “indirect or illustrative†(96). While one can certainly understand the over-exaltation of Jesus as the second person of the Trinity to the point where his earth life is utterly eclipsed in the shadow of later theological affirmations, there is little attempt on Evans part at balancing Christ’s two natures.The second possible point of contention is of a more theological nature, and it concerns Evan’s commentary on Jesus as ‘Messiah’ (86-87). While citing Albert Cleage’s ‘The Black Messiah’, Evans notes Cleage’s comments about Jesus being “a revolutionary leader, a Zealot actually committed to leading Israel, etc.†and states, “there is at least as much truth as there is hyperbole to [Cleage’s] position.†There is little evidence to support that concept as Jesus as a zealot or revolutionary, and Tom Skinner’s position (87) seems to reflect the standard messianic views of “Kyrios†in Judaism and have the general support of most NT scholars today. Also of note is that the major New Testament writers don’t appear to describe Jesus in such a way. Since Jesus is most probably not a zealot, one wonders to what extent one can validate Evan’s affirmative point about Cleage’s statement. It seems it would be more historically accurate to support Skinner’s more moderate approach to Jesus and Second Temple Judaism, rather than being seen as an “extreme†by Evans (87).The final comment is that I wonder to what extent the New Perspective on Paul could benefit (or be benefited by!) black theology. How would black theology take account of this dominant theological reconsideration, especially as regards the law? On account of this, where would St. Paul fit into Evan’s constructive theology, especially given Paul’s own autobiographical understanding (possibly Rom. 7 but especially Phil. 3:1-11) and his sufferings (2 Cor. 11:16-33)? St. Paul is mentioned several times throughout the textbook, but Jesus is clearly the hermeneutical key that Evans utilizes. On the other hand, one could envision N.T. Wright and Evans sitting down to discuss the finer points of grace and law, and I imagine both sides would be mutually benefited. One couldn’t dispute that the conversation between the two would be galvanizing.Mainstream evangelical theology hasn’t given black theology the time of day; this is to our disgrace. I hope that all evangelicals (progressive, moderate, conservative and fundamentalist) would read Evans with an openness to learn, to experience, and to utilize him and others in the construction of a theology of all and for all. It is firmly evangelical to seek the liberation of maligned social groups (such as minorities, those in poverty, women in the church) and Evans remains a force of change as we seek to right the wrongs of history. While I have some reservations involving some of his conclusions, Evans is impassioned, widely read (quoting Barth, Tillich and Fiorenza) and has written a helpful introduction to black theology; one that I wish I had read many years ago. I cannot wait to assign him as a required text when I begin to teach.

In his book, We Have Been Believers, James Evans seeks to examine the subject of Systematic theology from a uniquely African-American perspective. Part of the difficulty in doing this is that by its very nature this tradition does not have the history of formal theological development, rather the theology has arisen from practice and context rather than specific academic treatises. While it can be said that for the most part African-American congregations do not necessarily differ in a great deal of what can be called intellectual theology, and generally are aligned with denominations that themselves have a history of formal theological development, the great, the great difference in historical situation has radically impacted much of the actual interpretation and ?working out? of this theology. As a people who have been traditionally oppressed within this nation, an African-American perspective can offer a great deal of insight about the nature of the church, and is truly a valuable study in its own right.The difficulty with attempting to do a specifically African-American ecclesiology, states Evans, is that there cannot be located a specific ?African-American? church which could define the theology, rather these churches have a variety of theological traditions, customs and styles. Another difficulty is that the idea of community itself is such an inherent trait to African-American thought that typical doctrinal assertions simply are not adequate to describe the nuances of understanding. Because the theology has arisen out of a specific context, without a great deal of formal theological examination, the theology which is present cannot always be codified, and when it is it loses something in the process. The idea of having community is, according to Evans, an innate religious sensibility. There is a natural, deep-seated affirmation of the ?clan, group, or tribe?, understanding that only in community is there survival, prosperity, and sacredness of life. The massive oppression which came as a result of slavery and later from institutionalized racism enhanced these natural tendencies within the community, cementing the bonds of fellowship under persecution.Evans analyzes the various topics of systematic theology looking how those within the African-American community have developed a distinctness in practice and thought. For a basic introduction to this communities thought, as well as a great balance for the typical theological perspectives this is a great read.

We Have Been Believers PDF

We Have Been Believers EPub

We Have Been Believers Doc

We Have Been Believers iBooks

We Have Been Believers rtf

We Have Been Believers Mobipocket

We Have Been Believers Kindle

Posting Komentar